Ten days in Detroit provided me with some more insights into how the city works and what lies behind recent changes. Many conversations yielded deep insights, but also puzzled me with further questions and issues around the role of planners in processes of urban change and renewal. Time to wrap up some still preliminary and unfinished ideas.

It seems that there are four types of planning and planners:

1. Private companies

Many large-scale initiatives and changes refer to a small number of companies or individuals. The names of Dan Gilbert (Quicken Loans) and the Ilitch family (Ilitch Holdings) are omnipresent around downtown. They fund public spaces, public infrastructure (like the QLine), and organize urban life. When I hear of important businessmen supporting downtown life and encouraging their workers to live downtown, this equals public planning strategies in many cities. However, it also reminds me of 19th century industrialization in Europe where cities were built around industrial complexes with them caring for housing, services and life. I am struggling with evaluating such developments and the resulting huge reliance of urban development in single business models and individual businesspeople.

In a certain way, such companies and individuals filled in a void of public planning. Their actions are much like planning, extending from private properties to surrounding spaces and connections. This seems to follow a certain strategic idea and plan, but lacks public accountability and a focus on the whole territory of the city and region.

2. Foundations and Non-Profit-Organizations

Midtown Detroit has undergone a radical revival within only a few years. Large parts of this is devoted to organizations like Midtown Detroit Inc. and engaged individuals like Sue Mosey. Newspaper articles even name her as “Mayor of Midtown”. It is definitely amazing to see how much has changed due to their activities and how fast this change occurs. It brings back life to vacant buildings, to public spaces and to formerly empty streets. However, their area is limited and the gradient towards the surrounding neighborhoods seems to grow, in my very subjective view.

Detroit Future City is another example of a strategic framework as “a 50-year, highly detailed, long-term guide for decision-making by Detroit stakeholders, from elected officials to residents”. Their effort include many parts of a regular planning process, except that the result was not endorsed by any public authorities. The discussions have definitely been influential, but coherent implementation seems unlikely without broader support and buy-in.

3. Neighborhood and civil society organizations

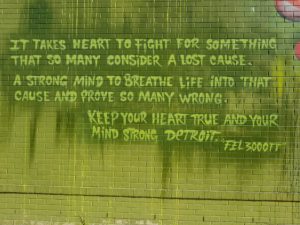

Detroit shows an amazing number of small-scale initiatives. They work on urban gardening, urban farming, sharing of infrastructure, or jointly using buildings and spaces. These are really agents for change in their neighborhoods. As a visible example, walking around Eastern Market on a market day shows a huge variety of local produce with numerous local producers. Many further examples are not obvious from the outside, like local community associations in areas that have lost large parts of their housing stock. However, many of these initiatives fill a void of public support. They may leave behind people that are not able to self-organize, like elderly or disabled people.

On the more organized scale, even the most deprived areas have local initiatives. They bind together local residents, businesses or artists. There is much to learn from how important networks of engaged people are for working with large-scale urban change and pressures. On the downside, some of these seem feel either pressured from recent developments or unheard by others. I have heard many examples of people whose house values have increased ten times in only 5-10 years. Prices are still comparably low in many places, but buying houses for few thousand dollars seems no longer possible.

With regard to planning, there are many neighborhood-based plans, often with support from foundations or other donations. Initiatives like “The HOPE Village Initiative” have produced plans with strategic goals, measures down towards implementation ideas. They are doing planning work for their own area, but often lack financial and/or legal means for implementation.

4. Public planning

Public planning has been phased out for some time during the bankruptcy of Detroit and seems to be slowly re-emerging. It is definitely one of the most challenging situations imaginable. I have heard of newspaper headlines like “fire a planner, safe a cop”. There is definitely lots of understandable truth in the opinion that public planning is not a basic function of society. Now that the situation changes, one can expect planners first as observers. However, it seems more urgent than ever to have good planning in these times where some parts of Detroit see a revival of businesses and growth of population again. It is then about connecting different pieces of change and ensuring that it is beneficial to the city and region as a whole.

Public planning works towards some integrated strategic framework or master plan. To date, it is more about certain neighborhoods or specific projects. I have often heard the term place-making for the focus of many planning efforts, both private and public. Difficult to imagine how to re-start with planning in a city after such large-scale failures of a city as a whole – not to speak about regional perspectives. My strong belief is that urban change needs to have an integrated vision, strategic framework and coherent planning. Change produces losers and winners, but planning can make these visible and can work towards a version of change that recognizes the diversity of people, communities and businesses. As soon as new interests for using spaces within Detroit emerge – which is currently happing – there are entry points for coordinated planning efforts.

Open question: Is place-making enough?

Having many places with specific qualities in a city does not yet build up a city. There is much to learn from how many very diverse actors engage in ‘their’ surrounding areas, may it be downtown, midtown or other neighborhoods. But: if we talk about the revival of a city, a city-wide perspective would be essential. I will be eager to learn during the next days what is happening in this direction and where the largest challenges are to be found…

Your impressions capture some of the paradoxes of planning in Detroit. On the one hand, Downtown and Midtown have many fantastic public spaces and programming supported by public-private partnerships. Rather than see it as a trade off to neglected neighborhoods, I see it as a consequence of a set of State and Federal policies. With regards to the public planning, the regional bodies (e.g. SEMCOG, RTA, GLWA, Metroparks, DIA, Zoo, AAAs) and the State of Michigan (e.g., DNR, MDOT) have their own planning functions within their respective domains. The Area Agencies on Aging are federally funded planning and grantmaking organizations that have a more regional scope–but there are three such agencies in Metro Detroit. The City of Detroit used to have an Arts Commission, but this was cut decades ago. The Kresge Foundation is funding the City of Detroit Planning Department to plan next steps for a new version of an Arts Commission, but how will this interface with the regional arts bodies as well as neighborhood level arts activities (e.g., Red Door in North End).